Why Amazon is not your biggest problem

The science of failure in retail

The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.

Neil DeGrasse Tyson, Astrophysicist.

The competitive world of retail has forged some of the greatest minds in business – warriors of commerce and hardnosed skeptics who can spot a ruse a mile away. Interestingly though, no one seems to have spotted a potentially mortal wound that has lingered unnoticed in many retail organisations for more than a decade.

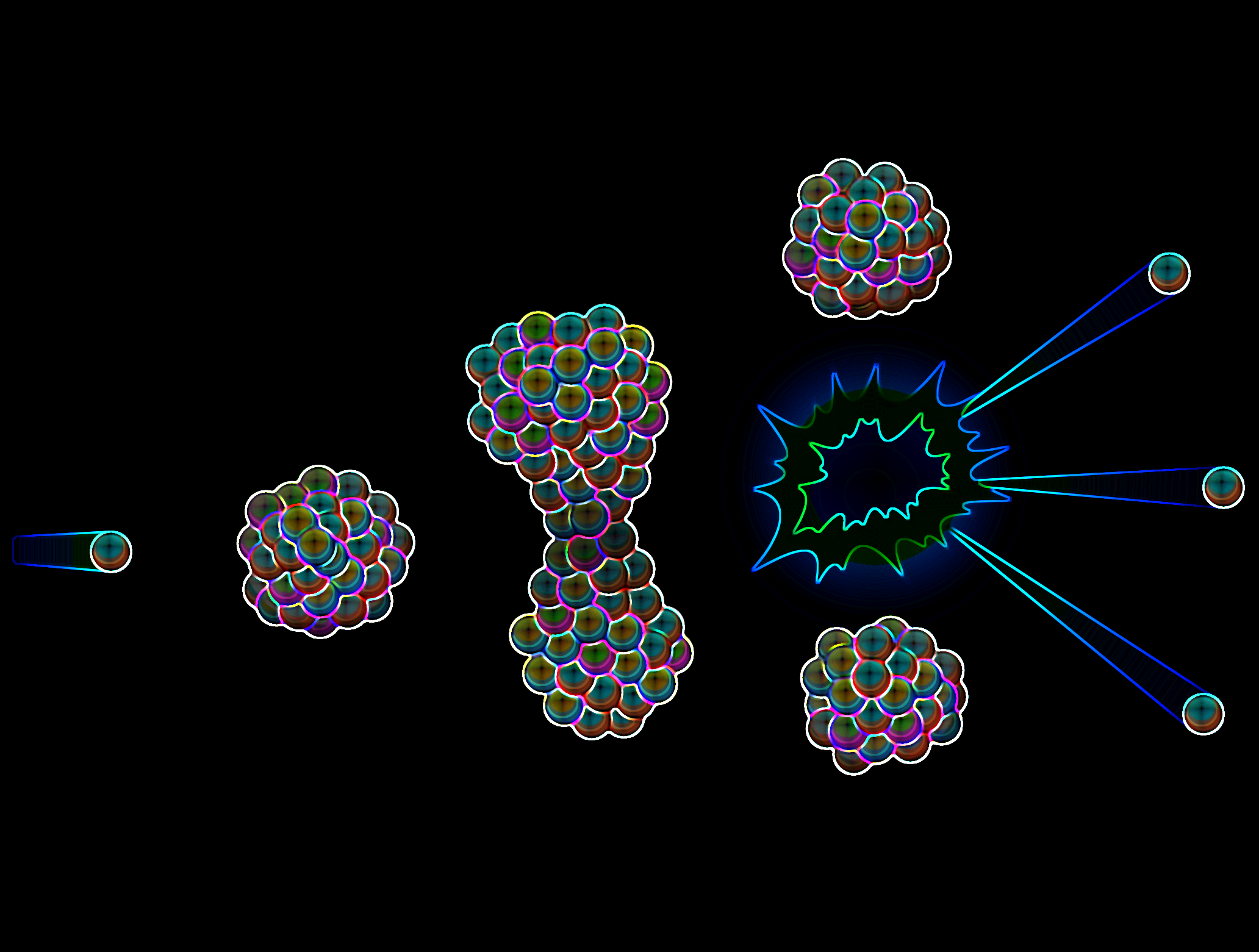

The infliction I speak of can best be described through science, specifically a principle known as the Chaos Theory. Shown in the diagram below, it illustrates the behaviour common in all dynamic, complex systems – retail businesses included. As a system (business) progresses on a solid trajectory of growth, ‘bifurcation’ occurs (essentially a fancy way of saying the division of something into branches or parts).

In the diagram, the business has split, either because of a formal spin-off or an internal fragmentation. This explains how this particular retailer ended up with two virtually disassociated concerns – one focused exclusively online and the other servicing the traditional brick and mortar business.

In itself, this divide can cause material operational incoherence, however, the real danger lurks further to the right. In dynamic systems, one division compounds exponentially, eventually leading to system (business) disintegration.

The bifurcation graph caught my attention because it so accurately reflects the internal fragmentation (the abovementioned “mortal wound”) that occurred within many retail organisations over the last ten years. The seeds for the split were planted somewhere around the year 2000, when the evolving internet started to give life to a new galaxy of retail possibilities.

This new dimension in retail was embraced with fervour by retailers, who invested not just truckloads of money but also high emotion into exploring the uncharted territory. As marked on the graph, somewhere along the line many retail businesses fractured into separate digital and ‘traditional’ parts, each taking on its own life and operating in increasing isolation.

The Chaos Theory tells us that unless retailers eliminate this internal divide through the reunification of the digital and physical parts of the business, further bifurcation will occur, e.g. by the emergence of a fast-growing wholesale business, home party plans, or a marketplace department. This fragmented focus will further destabilise operations until disintegration occurs.

This may sound dramatic, but only if viewed through the lens of a short-term horizon. With a longer trajectory in mind, the scientific principle will act with its ruthless inevitability. Only one method can arrest and reverse the slide towards the collapse: strong action from outside the system to reunify the business.

Notes from the field

Nearly half of the way into 2018, I see mounting evidence that fully re-integrating the online and physical parts of a retail business into a single enterprise is becoming increasingly urgent as a pre-requisite for continuing relevance.

Retail Directions started to alert retailers about the growing negative impact of the digital/bricks divide early last year. For example, after attending Shop.org in Los Angeles, I wrote an article about the urgent need for the retail industry to drop commerce/e-commerce distinctions – not just theoretically but operationally. The longer such splits endure, the harder they become to eliminate – as the earlier graph predicts.

Retail Directions MD, Andrew Gorecki reinforced this message at the AFR’s Retail Summit late last year – talking about Humans 2.0, the inherent online and store co-dependency, and the critical importance of promoting a cohesive Digital Path to Purchase across all channels, not just e-commerce.

Andrew pointed out that instead of thinking in terms of online and in-store sales, retailers would be better served by dissecting and analysing sales transactions as collected versus delivered – the latter being materially less profitable, though necessary to ensure a full omni-channel offering.

Once you start looking at your sales in terms of over-the-counter versus delivered sales, it becomes clear that retailers who have managed to shift e.g. 10% of their overall sales to online don’t really have any reasons to celebrate. Real growth in retail requires a bigger top line and greater market share across all channels.

Having since spoken about the topic with numerous retailers, technology and marketing experts, I’ve started to see signs that many industry leaders have now begun to seriously considering merging the e-commerce and marketing departments – to create a unified customer engagement team.

Worryingly, this type of thinking still remains far from universal. Despite the mounting evidence, many retailers continue to resist the transformation required to survive. For example, Myer recently announced an even more acute separation of its online and brick and mortar businesses. The question begs to be asked: why go against the trend and the laws of science?

The benefit of hindsight

A short trip down memory lane explains the intricate nature of the investment in e-commerce that many retailers now struggle to walk away from. As mentioned at the start, vast amounts of money have been spent, creating not only a commercial (depreciation still underway) but also highly emotional attachment in the process.

When trading online started to gain momentum about fifteen years ago, retailers began to hire specialists in the space, to develop their online business. E-commerce websites were opened, and a wide range of experimental initiatives were employed to grow traffic and sales.

In those early days, and it remains true today, the more brick and mortar stores a retailer had, the easier it was to make the new online channel work. After all, every storefront acted, and still acts, as a billboard for the brand – seeding awareness and fortifying trust.

Unsurprisingly, the entrepreneurial e-commerce departments reported massive gains, not unlike communist Mongolia in the early 60s, which boasted about 50% industrial growth after opening its second factory.

However, the extra logistics overhead usually remained buried within the general business, while the apparent low cost of operations, due to the absence of store rent and labour expenses was intoxicating. It looked like Eldorado had been found, putting a question mark over the other parts of the business.

Then, as online sales increased, retailers began to notice that the performance of their brick and mortar stores started to stall, showing weak or no sales growth, sometimes even decline. This reinforced the suspicion that online trading must be their saviour and the future of retail – it appeared to be growing fast and compensating for the shrinking traditional business.

Driven by such statistics, some retailers began to reduce their store footprint, while the e-commerce department expanded and became the darling of business owners and executive management. Traditional stores started to increasingly look like a liability. When such a mindset took hold within a retail enterprise, it usually meant a terminal diagnosis for the business’s commercial viability. The wound was ripped open with full force.

The good news: as hinted earlier, if an external force is applied to a dynamic system, the system can be suppressed to a degree, allowing the fracture to be eliminated and a steady business flow can be re-established.

Let’s examine a real case where the senior management of a specialty retail chain facing these challenges decided to step back and review their business operations from a holistic perspective.

External perspective and engineered re-unification

The executive team asked a question: how would an external expert view the situation?

The insights from this exercise were startling. The products sold by the retailer were all private label, so its customers couldn’t just go somewhere else to buy the same items at a better price – the quite successful online channel was merely diverting traffic away from the stores, with little gain in overall market share. Consequently, some of the depleted physical stores had to be closed, but online sales in their catchment areas dropped by nearly 20%. A vicious circle.

Naturally, a percentage of customers preferred to have stock delivered to their doorsteps, especially if the retailer was paying for the ‘free’ delivery. Needless to say, the impact of the e-commerce venture on the retailer’s bottom line was quite profound once the costs of unit-level picking, packing, shipment and returns (close to 50%) were factored in.

It became clear to the executive team that in their e-commerce and physical stores were competing rather than collaborating for the greater good of the business.

Accordingly, they made a bold decision: to restore business coherence and merge the marketing and e-commerce teams. The objective was to create a modern business that engages digitally with its audience, to sell as much stock as possible, preferably collected from stores to protect net margin.

If you think that such bold operational decisions remain isolated, look no further than Nordstrom in the US. This leading department store has deliberately stopped reporting online sales separately, recognising that measuring their team based on store vs. online sales, rather than total sales was harming its business.

The Nordstrom approach makes good sense. If your customers demand a consistent and seamless “one” brand experience, unifying the client engagement structure of the business becomes the only way to effectively meet and exceed such expectations.

A retail business must operate as one rather than two separate universes. A house divided against itself cannot stand. As shown on the graph earlier, without reunification further fragmentation and eventually business failure will follow.

As retailers accept the essential need to adopt the Digital Path to Purchase approach and re-integrate the business, the traditional divide between the ‘modern’ and ‘legacy’ parts of retail will be no more. With the benefit of hindsight, they shouldn’t have been divided in the first place.

The future demands a modern, digitally savvy and integrated retail enterprise, able to seamlessly nurture and delight its customers across all channels.